Emmaus; Nicopolis; 'Imwas Complete

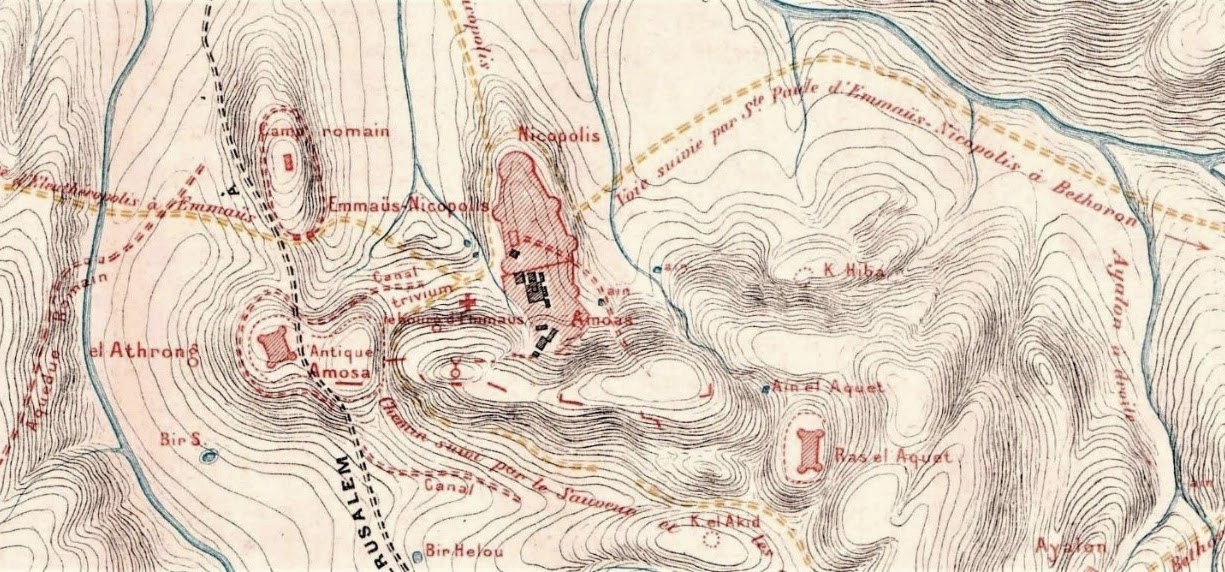

Localization

Site plan

Description

Emmaus is best known from Luke 24:13–35, which recounts a post-resurrection encounter in which two disciples meet Jesus on the road and, later, recognize him while sharing a meal in the home of Cleopas, a resident of the town. The linkage of this episode with Emmaus–Nicopolis has been questioned, however, on the grounds that the distance from Jerusalem seems excessive for a single-day journey; the village of Moza has therefore been proposed as an alternative setting. The origin of the toponym is unclear. Scholars have drawn parallels with Hebrew terms for thermal springs and with similarly named bath localities—such as Ἀμμαθοῦς near Tiberias and Ἑμμαθά close to Gadara. Archaeology corroborates the association with bathing facilities: Roman-period thermal installations were excavated by M. Gichon at Khirbet Sheikh Ubeid and Khirbet Aqed in the vicinity. No texts, biblical or otherwise, mention Emmaus before the Hellenistic era. The earliest citation occurs in 1 Maccabees (3:38ff), which situates Judas Maccabaeus’s victory over Gorgias near the hill of Emmaus. A subsequent notice (1 Macc 9:50ff) attributes the construction of a fort there to the Seleucid general Bacchides in 160 CE to monitor the activities of Jonathan, Judas’s brother. Josephus later reports that, toward the end of the first century BCE, Emmaus supplanted Gezer as the seat of a local toparchy. Under Roman rule it functioned as a polis, stood at a strategic road junction, and served as a garrison town. During the First Jewish Revolt it formed part of the military operations of Vespasian and Titus. According to Sozomenus, after his victory over the Jews Titus renamed the city Nicopolis; yet writers before the third century do not employ that name—neither Pliny nor Ptolemy does so—and the Peutinger Map, which preserves pre-Severan nomenclature for Palestine, labels the site enigmatically as “Avamante.” An Armenian recension of Eusebius of Caesarea relates that Sextus Julius Africanus, a Christian scholar who resided in Emmaus, petitioned the emperor Elagabalus (218–222 CE) to restore the town, at which time it received the name Nicopolis. Coinage of Elagabalus bears inscriptions confirming the name and is dated to the “Year Two” of the city. Although certain Flavian coins carry the legend “Nicopolis,” these may belong to Bostra or to Nicopolis ad Lycum. On balance, the change of name appears to belong to the reign of Elagabalus. Rabbinic literature mentions the place frequently, under varying forms—Pomais, Hamatha, Maus, Imunis/Imwis, Maos. From these sources emerge details about an ample water supply, an active market (notably in cattle), and a population that included Samaritans. The church of Emmaus is first noted by Paula during her pilgrimage of 385–386 CE. In the later Roman period, Saba founded a monastery at Nicopolis. A destructive earthquake struck in the eighth year of Anastasius (498 CE). John Moschus, the last Byzantine writer to refer to Emmaus, recounts the deeds of Cyriacus, a local brigand who led a mixed band of Christians, Jews, and Samaritans. Following the Islamic conquest, the settlement declined rapidly, though it saw temporary reoccupation in the Crusader era. Modern exploration began in 1875–1882, when Captain J. Guillemot excavated the ruins at ‘Imwas, commonly identified with ancient Emmaus–Nicopolis. Clermont-Ganneau and colleagues from the Survey of Western Palestine visited the site, produced a plan of the ancient church, and first reported a limestone capital bearing Greek and Samaritan Aramaic inscriptions. In the 1920s, the Dominicans F. Vincent and F.-M. Abel undertook further work, published in 1932, focusing on Khirbet el-Kenisah (“the ruins of the church”). The broader urban area remained largely uninvestigated, aside from later probes of aqueducts, wine presses, and tombs. A comprehensive survey of the site and its hinterland is still needed. The epigraphic record from Emmaus–Nicopolis is substantial. Most monumental inscriptions pertain to the Christian community (CIIP IV 3083–3090), several to Samaritans (CIIP IV 3079–3082), and a smaller group to the imperial cult and military units (CIIP IV 3077–3078). Further reading: CIIP IV Emmaus, Nicopolis (mod. 'Imwas), 441-449. Barag, D. 2009. Samaritan writing and writings, [in:] Hanna M. Cotton, Robert G. Hoyland, J.J. Price and David J. Wasserstein (eds.), From Hellenism to Islam. Cultural and linguistic change in the Roman Near East, 303-323. Eck, W. Koßmann, D. 2016. Emmaus Nikopolis: Die städtische Münzprägung unter Elagabal und angebliche Inschriften für diesen Kaiser. Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 198, 223–238. https://www.emmaus-nicopolis.org/english https://www.biblewalks.com/Emmaus